By Brendan Hussey

(I invited Brendan Hussey to generate this blog post after reading his comments to the post Closing the loop in the stem cell supply chain – presented graphically. It was clear that he had something fundamental to say about an important theory of aging and can write clearly and concisely. The only editing modifications I have made are minor corrections and implementing hyperlinks to referenced documents. Otherwise, the post is as written by Brendan. Also, I have posted a comment following the post. Vince)

In its simplest form this theory states that stochastic DNA damage (mutations) accumulate throughout life, progressively disabling cells, tissues and organs until they can no longer function. This is sensible when one considers “In principle, all other macromolecules are renewable, whereas nuclear DNA, the blueprint of virtually all cellular RNA and proteins, is irreplaceable; any acquired error is permanent and may have irreversible consequences2.” The primary sources of DNA damage are largely endogenous; metabolism and replication. Damaged differentiated cells are destroyed naturally through apoptosis (programmed cell death) or they may be frozen in a state of senescence. This is often not a problem in many tissues as these lost cells are replaced via stem cell populations (eg. gut epithelium) or through division of neighboring differentiated cells (eg. liver). It is commonly assumed that accumulation of DNA mutations in stem/progenitor cells is what leads to eventual tissue failure due to lack of tissue homeostasis. While this theory has strong support, the role that DNA damage plays is this homeostatic decline is less well established. As is often the case in biology, the issue is complex and reconciling the data inevitably incorporates arguments from many of the various treaties in this Anti-Aging Firewalls blog..

Chronological & Replicative Damage

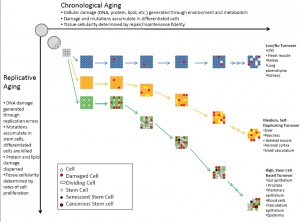

An important point of a lecture on mutation from my undergrad was to emphasize “Contrary to popular belief…Most DNA damage is caused by endogenous mutagens.” Consider that it often takes 20-30 years of heavy smoking to succumb to cancer; that is dying of exogenous influence. Endogenously generated mutations result from the most basic and essential of all cellular processes, metabolism and replication. Generally, metabolism as well as exogenous insults can be grouped into the category of chronological damage and replication can be grouped into replicative damage, which results in chronological ageing and replicative ageing 3, respectively (Figure 1). This distinction is a useful one as it allows us to categorize tissues based on their rate of replication (which is tied directly to cell turnover) and level of environmental exposure as well as rate and type of metabolism. This then allows us to predict the types of damage to which each tissue is likely to be vulnerable. As will be discussed in more detail later, tissue homeostasis stratagems depend on these variables and their interactions. For example, replication dilutes insults generated by chronological ageing, such as damaged proteins and lipids, which is important for highly metabolic cells or those with high levels of environmental exposure. However, the trade off is that replication increases mutations to DNA, which accumulate in dividing stem cells.

Metabolism continuously generates toxic byproducts such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and advanced glycation end products (AGEs) which damage macromolecules such as DNA. ROS and AGEs are major candidates for aging and discussed in more detail in the Oxidative Damage and Tissue Glycation sections of the firewalls treatise. Such metabolic stress generates ~70,000 mutations per day in the form of single strand breaks (SSBs), double strand breaks (DSBs), depurinations, oxidations, etc (ref. lecture from my undergrad). Other estimates are even higher at about 100,000 DNA damage events per cell per day12. Environmental insults such as radiation, carcinogenic small molecules and viruses also contribute to chronological aging. As such, chronological ageing affects all cell types, differing in intensity depending on the metabolic rate and type of various cells as well as the level environmental exposure and repair fidelity. For example, a highly metabolic tissue with high environmental exposure such as the gut epithelium would be expected to generate a large amount of chronological damage and hence age chronologically more quickly than other tissues. The gut epithelium has a very high cell turnover rate to compensate for such damage, as will be discussed in more detail later.

Replication is another large source of mutagenesis for cells, particularly for the DNA, and is especially a problem for high turnover tissues. A simple calculation from the same lecture illustrates this fact; “Consider just errors made during DNA replication….You each have 46 chromosomes = 6 X 109 bp DNA/cell. On average, a mistake is made once every in 109 bp of DNA copied. So, you have 6 mistakes/cell/division. You have ~1014 cells in your body that divide a minimum of once per year, so, a very conservative estimate is ~ 6 X 1014 mistakes per year…Or, at least 60 billion mistakes while in class for MBG*4270 today!!!” These are errors generated just by DNA polymerase, the DNA copying machine, and do not include the large mutations generated by reactivation of retroviruses and similar elements due to replication or the loss of telomere length (see the Telomere Shortening and Damage discussion). The actual error rate of DNA polymerase is 104 bp of DNA copied, but proofreading on the polymerase corrects many of these. Such DNA damage sensing and repair pathways are essential to cell survival. Not surprisingly these pathways are central to the DNA damage theory of aging.

Cellular Response to Mutation and DNA Damage

Before delving into mechanisms, a distinction must be made between two terms which are often used interchangeably; DNA damage and mutation11. DNA damage is a change to the DNA that compromises its functionality such as DSBs, SSBs, interstrand cross-links (ICLs) and telomere shortening, which are difficult to repair and are often cytotoxic resulting in cell death. Mutation, on the other hand, is a change to the coding of the DNA resulting in different functional products such as mutated proteins and can lead to numerous forms of cellular dysfunction such as cancer. Mutations result from polymerase errors in replication and from repair to DNA damage and are not inherently cytotoxic to the same extent as DNA damage. This distinction is central to cell survival and can predict cell turnover rates as well as susceptibility to cancer and aging.

A large amount of evidence for the DNA damage theory of aging comes from studies of humans and mice that have mutations in some aspect of the DNA sensing and repair pathways1. Mice have proved valuable models for disease in humans “In some cases, a mouse model even paved the way for identifying the parallel human syndrome… leaving no doubt that mouse models and human syndromes constitute valid ageing mutants.1” Mutations in genes which encode components of the sensing and repair pathways generate either, progeroid (pro-aging-like), cancerous, or both phenotypes depending on the cellular machinery affected.

The molecular mechanisms underlying these phenotypes hint at an interesting pattern and involve one of the most important DNA damage sensing and repair systems, the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway. Generally, damage to components which repair DNA damage often results in progeria, whereas damage to components which detect and repair mutations result in cancer. For example, defects in transcription joined NER (TC-NER), which repair damage in transcribed regions as transcription is happening, tend to cause progeria. Whereas, defects in global genome NER (GG-NER), which detect mutations anywhere in the genome at any time, often result in cancer. Defects to core NER components which are shared by both TC and GG-NER and other core cellular components such as DSB repair can cause both progeria and cancer. Progeria seems to be caused by defective repair machinery, that while able to detect mutation, cannot fix it defaulting to an apoptotic response to cytotoxicity via cellular mechanisms independent of NER. This results in increased tissue turnover as damaged cells are quickly discarded and replaced. Incidentally, progeroid syndromes of this type result in decreased incidence of cancer, as it is thought that cancerous cells cannot survive long enough to become malignant.

Cancer, on the other hand, seems to be the result of defective mutation detection machinery (not necessarily part of NER), which allows mutations to accumulate undetected, not triggering apoptosis. As aforementioned, tissue turnover initially helps prevent cancer development as differentiated cells which are harboring mutations are recycled before they can become malignant. Additionally, “…when oncogenic mutations induce pathological cell proliferation, rapid tissue expansion is originally limited by a corresponding increase in cell death. It is only when this natural compensatory mechanism is overcome by additional mutations that cancer progresses…5” Progeria and cancer can occur simultaneously depending on the type of DNA damage, the specifics of the pathways involved and importantly, their particular cell turnover rates.

The Role of Cell Turnover

Additional evidence for the link between progeria, cancer and cell turnover is evidenced in experiments involving p53, which promotes apoptosis. “The balance between deleting and preserving damaged cells appears to be particularly important for optimizing the trade-off between aging and cancer. This was elegantly demonstrated in a study by Tyner et al (2002) of which a mutant form of p53 showed constitutive activation. Heterozygotes between mutant and wild-type p53 showed increased p53 activity and had greatly reduced cancer incidence. However, they also showed faster aging. Their shortened life spans were accompanied by accelerated age-related reduction in mass and cellularity of various tissues, including spleen, liver, kidney, and testis. Accelerated age-related losses were also noted in skin thickness, hair growth, wound healing, and stress resistance (to anesthesia and to 5-fluorouracil treatment in hematopoietic precursor cells).2”

Another example comes serendipitously from what began as an interest in chronologically controlled knockout of the DNA damage response gene Atr. “Loss of Atr is toxic to proliferating cells… and when Atr was somatically excised in adult mice in a widespread manner by conditional inactivation, the vast majority of proliferating cells rapidly disappeared, producing marked intestinal atrophy and bone marrow hypoplasia 2 weeks after conditional activation. However, the animals survived this transient period of cell loss because rare stem cells that had not recombined the Atr allele replaced the lost cells. By 1 month after conditional activation, the mice appeared largely normal, with rapidly proliferating tissues that had been fully reconstituted by sporadic Atr-competent cells. Surprisingly though, these reconstituted mice then developed a marked progeroid phenotype a few months later, with osteopaenia, graying and loss of lymphoid and haematopoietic progenitors.15”

The same pattern is observed in aged mice, when challenged with radiation: “In the case of gut epithelial stem cells, even a very low dose (0.1 Gy) [of radiation] is sufficient to initiate apoptosis… It may be significant that, in aged mice, these stem cells, which exhibit some functional deterioration already, show increased levels of apoptosis in response to low-dose genotoxic stress…In general, in tissues where apoptosis is used to delete damaged cells, increased levels of apoptosis in aged organisms are likely to reflect higher background levels of accumulated cellular damage.2” Humans who have undergone chemo – radiotherapy again tie cell death back to ageing: “Indeed, long-term survivors of chemo- or radiotherapy show evidence of premature ageing.1”

The idea of a tradeoff between aging and cancer is compelling. The above examples suggest that increased cell turnover protects against cancer, with the cost of aging. At least for the cases in which apoptosis is a response to damage and mutation. While cell turnover rates can be modulated by DNA damage, tissues have inherent turnover rates ranging from very frequent to practically non-existent. For example the intestinal epithelium turns-over as a whole in about 5 days4, whereas most CNS neurons never turn over in the lifetime of the organism. Regarding cell turnover, “In humans, the magnitude of this flux is truly astounding—it has been estimated that each of us eradicates and, in parallel, generates a mass of cells equal to almost our entire body weight each year5.” Hence, one may expect than that tissues with the highest rates of cell turnover, such as the gut epithelium, to be protected from cancer and very low turnover tissues, such as cardiac muscle and the CNS, to be leading cancer incidence rates. However, what is actually observed is the opposite. In terms of cell division alone, a clear correlation can be found between tissues with the highest cell turnover rates and most cancers, when lung cancer is omitted due to smoking3,5,13. For example, prostate, breast and colorectal cancers lead incidence rates for combined men and women, which are among tissues with the highest cell turnover rates3,5. The trend continues with other leading cell turnover tissues such as lymphoid, uterine and skin as cancer leaders.

This correlation may at first seem to be at odds with the aforementioned experimental evidence. However, sensitivity to genomic stress resulting in increased apoptosis is not the same thing as natural cell turnover. As mentioned, co-occurring with progeria is decreased organ cellularity; decreased tissue homeostasis. Stem cells supply the reservoir of replacement cells is most tissues5, and the commonly observed increase in apoptosis of stem cell progeny in these models explains the decrease in tissue homeostasis. This is dissimilar from what we consider regular tissue homeostasis in which stem cell progeny maintain tissue homeostasis. It is this difference that can explain why increasing sensitivity to DNA damage and hence increasing apoptosis can prevent cancer at the cost of aging but why normal, homeostatic tissue turnover causes cancer. The sensitivity of progeria models to DNA damage and mutations prevents their progeny from surviving and manifesting cancer, but this is not the case in normal tissue turnover in which the progeny are less sensitive to damage and survive long enough to become cancerous. This is consistent with a model of ageing and mutation showing that “If mutations occur as a result of errors during cell division, the model suggests that a low cellular turnover rate protects both against aging and the development of cancer. On the other hand, if mutations occur independent from cell division (e.g. if DNA is hit by damaging agents), I find that a high cellular turnover rate protects against aging, while it promotes the development of cancer.10” This model can also help explain why tissues have different cell turnover rates. Tissues such as the gut epithelium, blood cells and skin have high environmental exposure (independent of cell division) and hence a high turnover rate protects them from ageing, at least initially as tissue cellularity is highly maintained. These are also the same tissues that lead the incidence rates of cancer. This tradeoff between growth /tissue homeostasis and repair/maintenance appears to be a case of antagonistic pleiotropy, the evolutionary genetics theory of selection for traits which benefit the young and fertile but compromise the heath of the old. Evolutionary theories are often evoked for explaining differences in cell maintenance as not much information currently exists as to why such differences arose.

The “Disposable Soma” Theory

Due to the genotoxic nature of cell division, the question arises as to why cells take the risk of dividing so often in so many tissues given that examples exist in which cell turnover is not required for tissue fidelity over the lifetime of the organism. Clearly, cellular maintenance can be such that error production is so low, or so well repaired, that cells need not turnover as is the case for CNS neurons. Furthermore, CNS related disorders are far from the leading causes of disability and death in old age14, demonstrating the functional efficacy of their maintenance. The efficacy of cellular maintenance mechanisms is further exemplified in germ cells, which are immortal and divide massive amounts, especially in mammalian males. This difference in germ cell and somatic cell maintenance is central to the “disposable soma” hypothesis. The disposable soma is an evolutionary theory that seeks to explain the disparity in cellular maintenance between germ and somatic cells by means of limited resource allocation between the two energetically intensive processes of reproduction/growth and repair/maintenance.

Kirkwood says it best; “Somatic maintenance needs only to be good enough to keep the organism in sound physiological condition for as long as it has a reasonable chance of survival in the wild. For example, since more than 90% of wild mice die in their first year…any investment of energy in mechanism for survival beyond this age benefits 10% of the population…Energy is scarce, as shown by the fact that the major cause of mortality for wild mice is cold, due to failure to maintain thermogenesis…The mouse will therefore benefit by investing any spare energy into thermogenesis or reproduction, rather than into better capacity for somatic maintenance and repair, even though this means that damage will eventually accumulate to cause aging…The idea that intrinsic longetivity is tuned to the prevailing level of extrinsic mortality is supported by extensive observation on natural populations…Evolutionary adaptations such as flight, protective shells, and large brains all of which reduce extrinsic mortality, are associated with increased longetvity”2. There are numerous lines of supporting evidence for the disposable soma theory and as such it is the most widely supported (see refs 1-3, 6, 7). Some examples include the highly conserved IGF-1/insulin pathway as well as mTOR signaling and the negative correlation between lifespan and fecundity.

The disposable soma theory can help explain (in an evolutionary sense) why some tissues, such as the CNS, do not turn over yet remain highly functional throughout life. The brain, as a defense from extrinsic mortality, is essential to reproductive success and as such is maintained with as much efficacy. This is part of the reason that the human brain is a huge metabolic expense; “Although the brain represents only 2% of the body weight, it receives 15% of the cardiac output, 20% of total body oxygen consumption, and 25% of total body glucose utilization.8” However, not dividing helps by removing a large source of mutagenesis as does being isolated from the external environment. Physiological constraints involved in path finding and wiring also help explain why most CNS neurons do not divide in adulthood. Few other tissues benefit from such metabolically expensive cellular maintenance, notably heart muscle, the retina, lung parenchyma and kidneys3. Notice that these organs are also very infrequently the cause of death or incidence of cancer in old age13, 14, suggesting immediate reproductive importance. Additionally, this suggests that highly proliferative tissues are the limiting factors in ageing and culprits of cancer, agreeing with aforementioned evidence relating cellular turnover to the tradeoffs between cancer and progeria. Inevitably, stem cells are suspect as they represent the reservoir for tissue homeostasis. As replication is one of the dominant forces introducing mutations in cells it is only a matter of time before progenitor cells accumulate enough mutations to become cancerous. This is the basis for the widely accepted, but not uncontested, stem cell theory of ageing.

Stem cells

The mere existence of post-mitotic tissues that are maintained for an organism’s lifespan seems to be in sharp contrast to the commonly held belief that aging is a result of stem cell depletion and subsequent lack of tissue turnover. Indeed, this issue is far from resolved. While “ [a]lmost every tissue studied has shown age-related decrements in the rate and/or efficacy of normal cellular turnover and regeneration in response to injury3”, “… there is no evidence that the maximal lifespan of any species is determined by declining stem-cell function or, conversely, that increasing the number or functionality of any single stem-cell population would extend lifespan.3” As reviewed in ref. 3, experiments with haematopoietic stem (HS) cells and skeletal muscle satellite cells show little intrinsic limitations in stem cell functionality that cannot be corrected with transplantation to young, stimulating microenvironments. “When HS cells have been tested in serial-transplantation experiments, complete reconstitution of the blood occurs over several lifespans in mice, and old HS cells are as effective as young HS cells at reconstituting the blood lineages after transplantation” and “…regeneration mediated by aged satellite cells was highly effective when the cells were transplanted into young animals as whole-muscle grafts. In fact, the results were indistinguishable from the regeneration mediated by grafting of young muscle.” This seems to be in contrast to the aging models presented earlier where increased cell turnover and stem cell depletion specifically, as in the Atr mouse, caused aged phenotypes.

However this does not disqualify stem cells as the cause of aging. It merely suggests that cell-autonomous properties of stem cells, such as DNA damage, may not be the driving force for ageing. This brings to light an important detail that needs to be stressed from the stem cell studies; the stem cells were fully functional when transplanted into young hosts BUT they were not acting youthful initially in their aged donors. They were in fact acting quite impaired in many measures from delayed and inefficacious migration to aberrant transcription profiles, all characteristics in aged individuals. This has been shown quite extensively elsewhere as well15, and also see Stem Cell Supply Chain Breakdown theory of aging. What this suggests is that it is not the stem cells which are damaged per se, it is their environment. In fact, it appears that any measure in which stem cells initially seemed to be impaired can be fixed with the right microenvironment.

In depth discussion of systemic messengers that influence stem cells to cause ageing is beyond the scope of this article but there are numerous candidates worth noting. One source of messengers are senescent stem cells. “Senescent cells increase with age in mice, non-human primates and humans…[and] secrete inflammatory cytokines and other molecules that alter tissue microenvironments.6” The role of cytokines suggests a potential role of immune cells, which is provocative given the number of age related autoimmune diseases, most prominently atherosclerosis, the leading cause of death in old age14 (also see the discussions on Chronic Inflammation, Immune System Compromise and Susceptibility to Cardiovascular Disease). Additionally, senescent cells may alter stem cell proliferation by competing for soluble small molecules such as members of the Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF- β)and Wnt families, as is seen in drosophila models (see ref 5). Additional evidence comes from the fact that, “In mammals, circulating levels of Wnt signal proteins increase with age, and this increase triggers muscle stem-cell ageing.7” TGF- β family members also play a role in mammals “with the identification of myostatin, a mammalian member of the TGF-β superfamily… This molecule is produced by adult skeletal muscle, circulates in the blood, and limits muscle fiber growth.5” Along the same lines of evidence for endocrine regulation is liver homeostasis. “A recent study suggests that adult liver homeostasis and regeneration is controlled by a similar mechanism of growth regulation. Bile acids are synthesized from cholesterol in the liver, secreted into the intestine to aid in lipid digestion, and then returned to the liver via the circulatory system. When liver function is compromised, circulating bile acid levels become elevated.

Intriguingly, Huang et al. recently found that bile acid triggers liver regeneration in mice through activation of a nuclear receptor signaling pathway… This observation leads to a simple model in which nuclear receptors regulate liver size by sensing its functional capacity. When liver injury or damage leads to a bile acid buildup, these receptors promote liver growth until normal hepatic function is restored and bile acid levels return to normal.5” This example is particularly intriguing as it ties in with the leading causes of death in old age, specifically the role of cholesterol and lipoproteins in the various forms of cardiovascular disease14. Furthermore, “[w]ith regard to the effects that the accumulation of senescent cells may have, there is evidence that the accumulation of senescent cells plays a role in liver fibrosis…, in immune dysfunction …, osteoarthritis … and in the development of atheroma.16” Finally, one cannot speak of systemic messengers without at least mentioning the IGF-1/insulin pathway as it is foundational to all ageing research and discussed in detail elsewhere1-3,6,7,12,15,16.

Implications for Ageing Interventions

As a whole, the DNA damage theory of ageing has implications for stem cell treatments, especially those intending to utilize induced plutipotent stem cells (iPSCs) as described in the Stem Cell Supply Chain Breakdown theory of aging. One issue is most iPSCs are derived from differentiated somatic cells such as the commonly used fibroblast. Fibroblasts are highly replicative and unsurprisingly display exponential increases in DNA damage markers with age resulting in senescent cells constituting as many as 35% of fibroblast populations in aged primates17. This accumulated DNA damage and increased sensitivity to senescence may be one reason why iPSC induction efficiencies are so low and iPSCs show impaired proliferative capacity and early senescence18. Furthermore, fibroblasts are one of the better donors for iPSC induction besides more pluripotent progenitors19, suggesting that many other tissues may have even more accumulated DNA damage that hinders their survival. This is supported by the study that generated the first all iPSC mice, which not only showed very low survival rates past early embryonic stages but more importantly that iPSC lines derived from the youngest donor cells had the highest survival rates20. When one considers these experiments in light of the DNA damage theory of ageing, it appears that supplementing dwindling stem cell populations with iPSCs derived from aged differentiated somatic cells as a form of treatment for longevity promotion would be counterproductive. In order for this type of therapy to be effective, cells with very little DNA damage should be stored and expanded selectively for therapeutic needs for individuals throughout their life. One option is embryonic-like cells harvested very early in life as these cells would harbor the least amount of DNA damage and hence offer the most consistent and safe regenerative potential.

Concluding Statement

To summarize, “…current theoretical understanding suggests that, as cells age, they tend to accumulate damage. The rate at which damage arises is dictated, on the average, by genetically determined energy investments in cellular maintenance and repair, at levels optimized to take into account of evolutionary trade-offs. Long lived organisms make greater investments in cellular maintenance and repair than short lived organisms, resulting in slower accumulation of damage. In order to manage the risk presented by damaged cells, particularly the risk of malignancy, organisms have additionally evolved mechanisms, such as tumor suppressor functions, to deal with damaged cells. The actions of such ‘coping’ mechanisms will frequently involve second tier trade-offs.2” A primary example is cellular turnover, which results in such trade-offs between cancer and ageing. As such, high cell turnover tissues are the limiting factors in the DNA damage theory of aging, as exemplified by the leading causes of death from cancer. Dysregulated stem cells form the heart of failing tissue homeostasis but debate remains on the role of DNA damage in these stem cells. That the local niche environment or other soluble messengers have such a strong influence on stem cells suggests endocrine dysregulation and systemic decline as prime candidates for ageing. Additionally, leading causes of natural, “old age”, death such as atherosclerosis and other forms of cardiovascular disease do not clearly involve DNA damage. It is also important to note issues with applications in this area. From what we understand about the accumulation of DNA damage in differentiated somatic cells, care should be taken when considering the use of iPSCs derived from such cells for regenerative purposes.

References

1. Garinis GA, van der Horst GT, Vijg J, Hoeijmakers JH. DNA damage and ageing: new-age ideas for an age-old problem. Nat Cell Biol. 2008 Nov;10(11):1241-7. Review.

2. Kirkwood TB. Understanding the odd science of aging. Cell. 2005 Feb 25;120(4):437-47. Review

3. Rando TA. Stem cells, ageing and the quest for immortality. Nature. 2006 Jun 29;441(7097):1080-6. Review

4. Blanpain C, Horsley V, Fuchs E. 2007. Epithelial stem cells: turning over new leaves. Cell 128:445–58

5. Pellettieri J, Sánchez Alvarado A. Cell turnover and adult tissue homeostasis: from humans to planarians. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:83-105. Review

6. Vijg J, Campisi J. Puzzles, promises and a cure for ageing. Nature. 2008 Aug 28;454(7208):1065-71. Review.

7. Kenyon CJ. The genetics of ageing.Nature. 2010 Mar 25;464(7288):504-12. Review.

8. Book Chapter. Brain Energy Metabolism. An Integrated Cellular Perspective. Pierre J. Magistretti, Luc Pellerin, and Jean-Luc Martin. From Psychopharmacology – 4th Generation of Progress, Floyd E. Bloom, MD & David J. Kupfer, MD

9. Yang J, Benyamin B, McEvoy BP, Gordon S, Henders AK, Nyholt DR, Madden PA, Heath AC, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nat Genet. 2010 Jul;42(7):565-9

10. Wodarz D. Effect of stem cell turnover rates on protection against cancer and aging. J Theor Biol. 2007 Apr 7;245(3):449-58.

11. Hoeijmakers, J.H., 2007. Genome maintenance mechanisms are critical for preventing cancer as well as other aging-associated diseases. Mech. Ageing Dev. 128, 460–462.

12. Lindahl, T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature 362, 709–715 (1993).

13. U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2007 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2010. Available at: www.cdc.gov/uscs.

14. World Health Organization (2004). “Annex Table 2: Deaths by cause, sex and mortality stratum in WHO regions, estimates for 2002” (pdf). The world health report 2004 – changing history.

15. Sharpless NE, DePinho RA. How stem cells age and why this makes us grow old. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007 Sep;8(9):703-13.

16. Faragher RG, Sheerin AN, Ostler EL. Can we intervene in human ageing? Expert Rev Mol Med. 2009 Sep 7;11:e27

17. Herbig U, Ferreira M, Condel L, Carey D, Sedivy JM. Cellular senescence in aging primates. Science. 2006 Mar 3;311(5765):1257

18. Feng Q, Lu SJ, Klimanskaya I, Gomes I, Kim D, Chung Y, Honig GR, Kim KS, Lanza R. Hemangioblastic derivatives from human induced pluripotent stem cells exhibit limited expansion and early senescence. Stem Cells. 2010 Apr;28(4):704-12

19. Ghosh Z, Wilson KD, Wu Y, Hu S, Quertermous T, Wu JC. Persistent donor cell gene expression among human induced pluripotent stem cells contributes to differences with human embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2010 Feb 1;5(2):e8975

20. Zhao XY, Li W, Lv Z, Liu L, Tong M, Hai T, Hao J, Guo CL, Ma QW, Wang L, Zeng F, Zhou Q. iPS cells produce viable mice through tetraploid complementation. Nature. 2009 Sep 3;461(7260):86-90.

Brendan Hussey is a B.Sc in Molecular Biology and Genetics, minor Neuroscience, University of Guelph. His e-mail is bjohnhussey@gmail.com.